The global economy’s insatiable appetite to consume natural resources and materials is interlinked with the triple planetary crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste.

According to the Global Resources Outlook 2024, nearly 55% of all greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and 40% of particulate matter-related health impacts are linked with extraction and processing of natural resources. Similarly, material use, driven mostly by the built environment and mobility sectors, has tripled in the last 50 years, rising faster than an increase in societal wellbeing (Global Resources Outlook, 2024).

In this regard, high-income countries, including the European Union (EU), are more material-intensive economies per capita. Unsurprisingly, these countries also contribute 10 times more to climate-related impacts than low-income countries (Global Resources Outlook, 2024).

EU economy is material-intensive

The EU, for instance, consumes over 8 billion tonnes of materials annually (EEA, 2024). Out of this, 5 billion tonnes were utilised to meet the citizens’ needs in 2022, of which 35% became waste, the remaining 3 tonnes are locked up as material stock in the economy, thereby unavailable for immediate reuse or recycling. Put simply, keeping materials in use for a long time is good for making things last longer, but it also means we’ll have to wait decades before they become available for reusing and recycling. This situation poses challenges for the EU’s sustainability ambitions as circular economy policies need to account for recirculation planning and resource extraction, in short and long-term, the EEA report states.

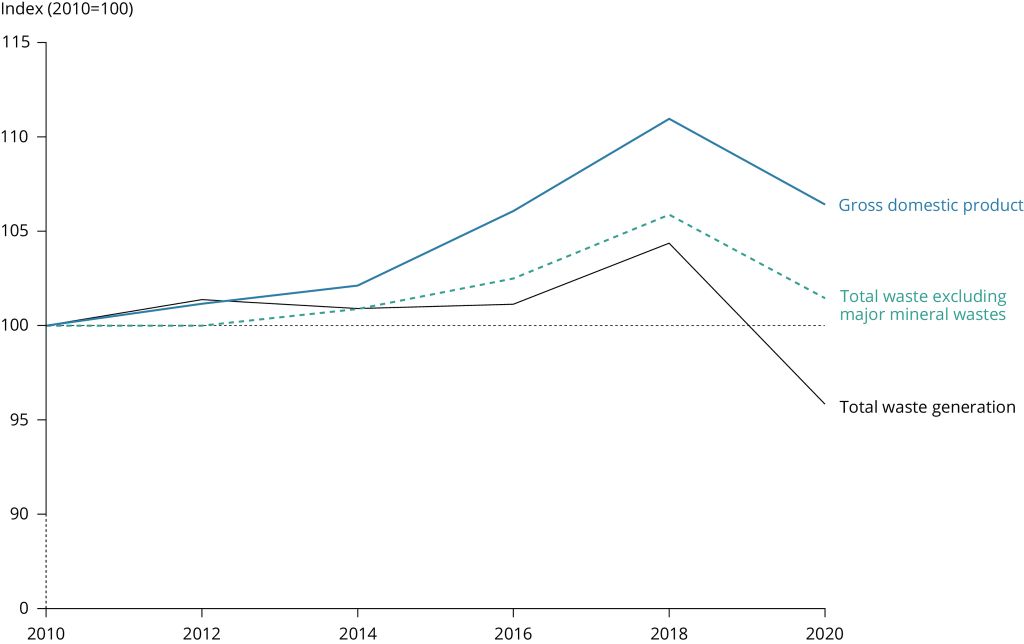

Material intensity notwithstanding, Europe predominantly follows a linear (take-make-use-dispose) model in which products are usually mass-produced and have a short life span before being chucked into the bin. Despite a decrease in waste generation between 2018-2020 owing to the pandemic and economic slowdown, per capita waste generation is unlikely to significantly decrease by 2030 (EEA, 2023).

Recycling alone won’t take us out of this mess

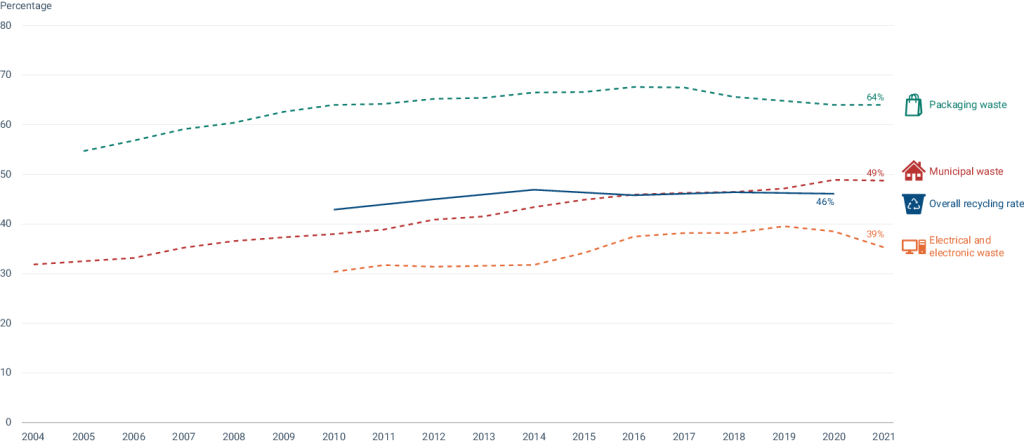

And recycling alone can’t be the solution to the waste problem, even though it has grown in the last few years. Although Europe’s waste collection targets (90% +) are way above the global average (75%) (GWMO, 2024), the recycling rates have stagnated at less than 50% over a decade between 2010-2021, as evidenced in the graph below (EEA, 2023). Thus, increasing quantity and improving waste quality remains a challenge.

EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan is a step in right direction

However, the EU’s binding recycling targets are driving a positive trend towards slowly rising recycling rates in general (EEA, 2023). At a systemic level, to pivot from trend of intensive material use, the EU is moving from a linear model towards a circular (reduce, reuse, repair, recycle) model, acknowledging that recycling alone won’t take the bloc out of this mess. One of the most important aspects of this transition towards circularity is the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), one of the key pillars of the European Green Deal.

The circular economy approach – which focuses on maximising the value of resources for as long as possible – combined with other initiatives in the Green Deal could potentially decouple resource use with economic growth and linked environmental impacts, thereby tackling the triple planetary crises.

It also offers greater strategic autonomy by way of increasing the EU’s material self-sufficiency (EEA, 2024).

EEA report calls for systemic shift towards high-quality recyclates

Relatedly, the EEA’s latest report calls on the EU to fast-track better waste management practices, such as taking urgent measures to focus on improving the quality of the recyclates to compete with virgin feedstocks in the marketplace and ensuring the marketplace for secondary raw materials functions, in practice.

More importantly, for circular economy to work at scale, substantial quantities of high-quality secondary raw materials need to be churned out for productive usage (EEA, 2024).

How RECLAIM Project aims to enhance waste sorting

Responding to the EU’s call to increase quantity and quality of recycled waste, the RECLAIM Project, a Horizon Europe funded initiative, was ínitiated in 2021 to address this challenge.

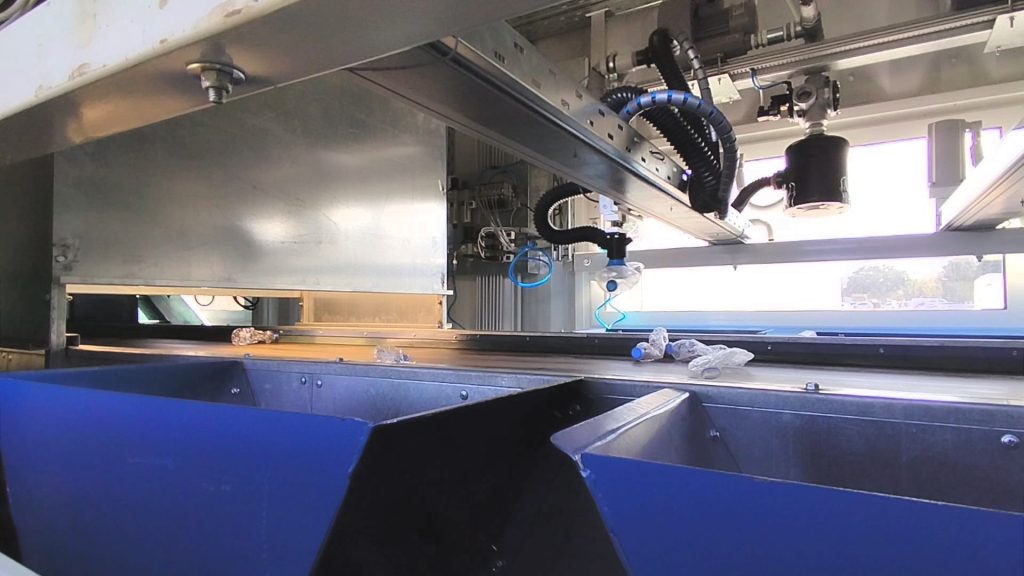

The project, is developing a low-cost, easy-to-install Artificial Intelligence-powered portable robotic material recovery facility (pMRF) that can be deployed anywhere, but particularly in smaller, less accessible areas, and will enable on-site, close-to-source recovery of recyclables.

Read our Blogs section for more insights

Advanced separation systems, such as low-cost, modular robots equipped with specialised grippers, can easily pull out many different material types. This, combined with state-of-the-art imaging technologies (RGB and Hyperspectral imaging), and artificial intelligence (AI), allows fast, accurate and adaptable sorting that will significantly accelerate local-scale material recovery activities with industrial-level efficiency. While the trend of employing light, flexible and portable waste management units is not new, to date these systems have not offered smart high-tech solutions that could significantly enhance their productivity. As a result, waste in these niche sectors is still being sorted manually.

Click here to see our project progress

One of the biggest advantages of the prMRF is that it can be deployed anywhere, and, in that sense, adopts a decentralised approach to maximise material recovery beyond the current, urban-centered focus areas, allowing for full scale material recovery, even in remote areas.

Three material recovery scenarios to maximise recycling

Our project explores three material recovery scenarios to increase the quantity and quality of recyclable materials:

- Scenario 1: Material recovery from mixed recyclable streams; most challenging due to high material complexity;

- Scenario 2: Cleaning of citizen-separated material specific streams;

- Scenario 3: Immediate, close-to-source material recovery

In essence, RECLAIM will assess how prMRF operations handle different types of waste, both mixed recyclable and material-specific streams. It will use positive separation for mixed recyclable waste and negative separation for material-specific streams. This poses a big challenge due to the complexity of materials, which the project will continuously tackle. Moreover, the project will investigate the potential of using portable prMRF technology for local robotic material recovery and sorting near the source. It will compare this approach’s efficiency with current practices.

While this touches upon the supply side of secondary raw materials, the project will also ensure the demand-side is taken care of through consumer behaviour change and awareness raising initiatives, such as the RECLAIM Recycling Data Game (RDG).

The RDG employs citizen science methodology to collect scientific data to train Artificial Intelligence (AI) for effective material recovery, thereby promoting better material sorting based on accurate identification of stuff. In the RDG, developed by the University of Malta, citizens take part in project activities by participating in a game to identify different types of post-consumer waste, training the AI-module to become more effective in identifying plastic waste for recycling and waste management.

Conclusion

With the support of these technologies, we will increase the quantity and improve the quality of recyclable materials derived from municipal solid waste (MSW), thus contributing to the EÚ Green Deal objectives and the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP).